Preamble

This page is my personal tribute to the Polish author Stanisław Lem, who I believe to be one of the greatest writers in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Through a short casual essay and some book reviews composed in my spare time I hope to convince readers that Lem is so versatile that his works effectively form a superset of the works of many more famous authors. Is his writings, Lem explores almost every major issue of science, ethics, sociology and philosophy, often using black comedy, mystery, parodies and metaphors.

Since I discovered Lem in 1979, his writings have been my constant companion and a source of relaxation and inspiration, and he slowly has become my yardstick of SF quality. Almost every time I read a book, or see a movie or TV show on SF I find myself thinking "Lem has already written about that, and it was better".

Lem's works must surely strike a resonance in the minds of people who have an interest in science. Lem has a well-rounded knowledge of many areas of science and he weaves his polymath skills into his works in such a way that they have more depth than is normally found in the SF, fantasy and detective output of other more famous specialist authors in these genres.

This is a hobby "fan" page, so I will welcome feedback of any type regarding errors or omissions. Even disputes about my opinions will be welcome.

Measuring Lem

If the greatness of a science fiction can be measured by a long career, diverse subject matter, diverse styles and numbers of prints and translations, then Stanisław Lem's name will easily percolate up with the legendary names like Clarke, Asimov, Heinlein, Van Vogt, Farmer, Herbert and Bradbury (amongst others). If diversity is a key attribute of greatness, then Lem can surpass many of the legends of science fiction.

![]() For me, what separates Lem from the other famous names is the astonishing diversity of

subjects and styles he has encompassed and experimented with over the last 50 years. Clarke and Asimov for example are prolific authors who are instantly

recognisable and occasionally make excursions into the popular science or detective genres, but have they ever written such things as cybernetic fairy tales,

book reviews of nonexistent books, excerpts from encyclopedias of the future or dialogues with omniscient artificial brains? Well...Lem has, and he's explored

these strange subjects with such penetration, wit and insight that one is left stunned.

For me, what separates Lem from the other famous names is the astonishing diversity of

subjects and styles he has encompassed and experimented with over the last 50 years. Clarke and Asimov for example are prolific authors who are instantly

recognisable and occasionally make excursions into the popular science or detective genres, but have they ever written such things as cybernetic fairy tales,

book reviews of nonexistent books, excerpts from encyclopedias of the future or dialogues with omniscient artificial brains? Well...Lem has, and he's explored

these strange subjects with such penetration, wit and insight that one is left stunned.

Lem's works can be read at many levels, and this is another quality that sets him apart from many other science fiction authors. Some common themes that run through Lem's works are far from trivial: questions about life, thought, information, intelligence, "first contact", chance, randomness, bureaucracy, morality, reality and dreams. Authors such as Phillip K. Dick, J.G. Ballard, Robert Heinlein and A. E. Van Vogt specialise in working with some of these themes, but only Lem has explored them all with an insight that often leaves the specialists floundering.

I think the most thought provoking and multi-layered of Lem's works are the absurdist ones such as The Star Diaries, The Cyberiad and Mortal Engines where black humour and wry tales are spun with science and moral dilemmas in strange circumstances. In these stories we are thrown into fairy tale universes inhabited by capricious characters and bizarre cybernetic geniuses who embark upon fantastic adventures.

Common Themes

Lem is at his most profound—and sometimes most disturbing—when he examines the question "what is life?". In some of his stories we meet cybernetic minds, artificial people, simulated kingdoms and resurrected souls; and the simmering question is always "when is something alive?". This is illustrated by a touching moment in The Cyberiad where Klapaucius the constructor admonishes his colleague Trurl for constructing a simulated kingdom of tiny beings for an exiled cruel tyrant:

"Trurl! Our perfection is our curse, for it draws down upon our every endeavour no end of unforeseeable consequences!" Klapaucius said in a stentorian voice. "If an imperfect imitator, wishing to inflict pain, were to build himself a crude idol of wood and wax, and further give it some makeshift semblance of a sentient being, his torture of the thing would be a paltry mockery indeed! But consider the next sculptor who builds a doll with a recording in its belly, that it may groan beneath his blows; consider a doll which, when beaten, begs for mercy, no longer a crude idol, but a homeostat; consider a doll that sheds tears, a doll that bleeds, a doll that fears death, though it longs for the peace that only death can bring! Don't you see, when the imitator is perfect, so must be the imitation, and the semblance becomes the truth, the pretense a reality! Trurl, you took an untold number of creatures capable of suffering and abandoned them forever to the rule of a wicked tyrant....Trurl, you have committed a terrible crime!"

If only Stephen Spielberg was capable of catching such concepts and sentiment in his appalling 2001 movie AI (Artificial Intelligence), which failed at every possible level in attempting to examine man, machine and intelligence (if that's what he was trying to do, as the movie was such a jumbled mess that I'm still not exactly sure what the point of it was).

Another common theme in Lem's work is "first contact". This theme has been explored by countless authors and script writers over the last 50 years or so, but I think Lem has stretched the theme to the breaking point of the imagination, and when be combines it with his favourite question "what is life?" the results can be startlingly original and disturbing. In Solaris we encounter what seems to be a planet covered in a living ocean and communication with it takes a very frightening form. In Fiasco we meet aliens who are so utterly incomprehensible that all frames of reference are shattered. In His Master's Voice we find information (intelligence?) encoded in the background neutrino radiation of the universe. In The Invincible we are confonted with clouds of metal insects over the desolate ruins of an ancient mysterious civilisation.

Lem likes the detective story genre and he blends it elegantly with SF, His "first contact" stories contain human investigators and explorers who are confronted with alien mysteries that require the greatest imagination and discipline to unravel. Lem illustrates how scientific progress is like detective work.

Book Reviews

Following are my reviews and comments upon some of Lem's novels, presented roughly in descending order of my familiarity with them. I hope my comments upon Lem's works will help convince you that he is the greatest science fiction writer. If a book is not mentioned, then it means I (very sadly) do not yet own it. Click on the book covers to pop-up enlargements.

As an aside: I think the translator Michael Kandel deserves glowing admiration for his translations of Lem's works from the original Polish. I can't read Polish to make comparisons, but I'm quite capable of imagining how difficult it would be to take such unconventional works full of puns, prose, science and artificially constructed words, and translate in such a way that the author's intent and style is preserved. Kandel must surely have done an astonishingly good job.

|

|

|

One day Trurl the constructor put together a machine that could create anything starting with n. If you can understand the strange appeal of this opening line then you are destined to be a Lem fan. In this book we join the "cosmic constructors" Trurl and Klapaucius as they romp around the universe bumbling their way through gargantuan cybernetic feats. It's a blend of folk stories, fairy tales and mythology mixed with higher mathematics, probability and philosophy. Our constructors are cybernetic machines, which is easily overlooked at times, but it gives the stories an other-worldly feel unlike any other work I have read. Some of the plots include:

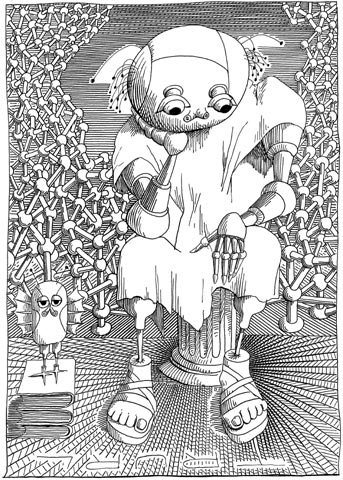

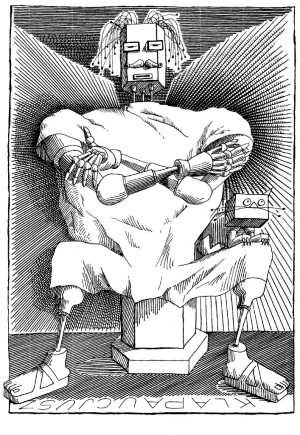

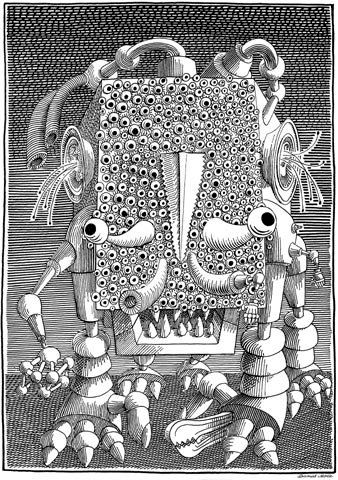

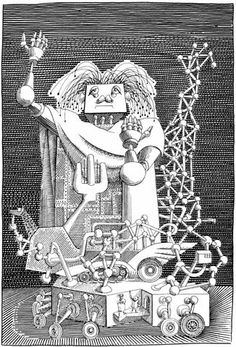

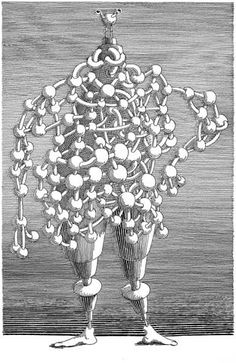

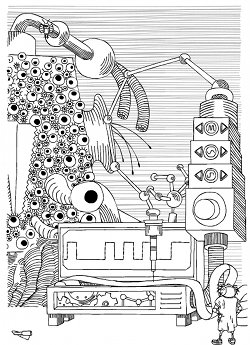

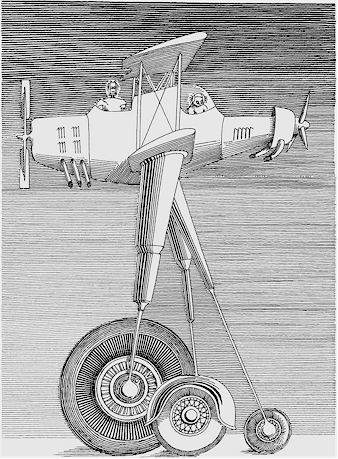

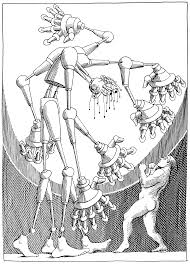

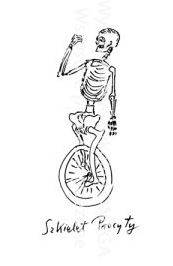

This touches on about half of the stories in the book. The other stories are so unconventional that it's very difficult to summarise the plots in a meaningful way in a short space. The stories in The Cyberiad are the ones that best exemplify the way Lem can be read at many levels. Superficially they could be seen as absurd fairy tales, but lurking beneath are sobering and penetrating metaphors for everything that is important in human science and philosophy. The illustrations of Daniel Mroz that are scattered through the book capture the feel of The Cyberiad wonderfully and a gallery of his hilarious drawings can be found on Lem's web site. Given that the book was originally written in Polish and translated by Michael Kandel into English, I remain absolutely gob smacked as to how the story of the electronic poet was translated, especially this part where Klapaucius sets a challenge to Trurl's poetry spouting machine:

"Have it compose a poem—a poem about a haircut! But lofty, noble, tragic, timeless, full of love, treachery, retribution, quiet

heroism and in the face of certain doom! Six lines, cleverly rhymed, and every word beginning with the letter s!!" How on earth was that piece of linguistic gymnastics translated from Polish to English? If anyone knows, please get in touch with me. Update (May 2005) - The answer is below.

I can currently only read about 1 word in every 50 of the Polish, but I'm very proud to have an original Polish version of my favourite Lem novel in my collection. Now I have to find a good English-Polish dictionary, or find someone nearby who will give me cheap Polish language lessons! This book has many more chapters than the English editions. The table-of-contents shows that stories from Mortal Engines open the book, followed by the Cyberiada stories, and it finishes with a few others stories whose titles I am currently unable to match with English equivalents. Upon receiving the book, I flipped through the pages looking for the famous rhyming six line poem (see above) to see how it appears in Polish. Here it is:

Cyprian cryberotoman, cynik, ceniąc czule Despite not being able to read the Polish poem, I can tell that Kandel has invented a new poem subject for the English version. Thanks to Michael Kandel who emailed me in April 2005 to tell me how he enjoyed by comments about Lem's works and my praise of his translation of the electronic poet. After overcoming the shock of being contacted by Kandel directly, I replied and asked him how the original Polish poem translated and he supplied the following (but note the comment after the poem):

Cyprian the cyber sex fiend and a cynic, appreciating tenderly the miracle of the dark body of the Negro daughter of Caesar,

constantly wove charms with a lemon. She blushed all over, silent, waiting every day, suffering, watching ... Cyprian kisses her aunt, have

abandoned the black beauty! A Polish friend pointed out that Michael made a hilarious accidental mistake with one word in the translation. My friend found the Polish word cytrą translated to zither in her dictionary (but I'm guessing the word lyre might also be acceptable). Thanks again to Michael for his legendary Lem translations. |

|

|

|

The adventures of Ijon are so complex that Lem claims the science of Tichology was created just to map his movements in space and time. A few months ago I saw a challenge on Lem's web site for someone to write Ijon's first adventure, and if you are a true Tichologist then you will understand why this task is on a par with creating a general theory of everything (which one of Ijon's ancestors attempted). One of my favourite stories is when Ijon's mentor Professor Tarantoga investigates attacks on ships in the commercial space lanes and finds that sentient space-flying potatoes are the perpetrators. In other stories, Ijon tampers with the evolution of a distant planet, he goes squamp hunting on Arduria, he meets himself in a time-loop, he dreams he's Earth's galactic ambassador and finally hallucinates the company of his complete ancestry on a lonely journey. There is a touching moment in one of Ijon's longest journeys in his rocket where he becomes weary and tired for his home on Earth. He accidentally shakes a tiny pebble of terrestrial soil out of his shoe, and clutching this precious piece of his home world he gains the strength to endure the rest of the journey. You should read this book while on holiday listening to the gentle whirring of the octopockles. |

|

|

|

Warning: Plot spoilers may follow. I struggled through the first 40 pages of chapter one and stopped, exhausted and disappointed. I felt like I was reading the oldest of old fashioned realistic science fiction. We follow the very, very "dry" adventures of a rescue mission on the icy surface of Saturn's moon Titan. I was reminded of the tedious documentary style of Arthur C. Clark's 3001 The Final Odyssey which I had read a couple of months earlier. In both cases I use the expression "dry" to mean that the descriptions of people and technology are so tediously detailed that it's like reading an edition of Popular Mechanics . It's a coincidence that I had read 3001 a short time before Fiasco, as I will return to making comparisons between them later. Overall, I felt shocked to think that after so many decades of incredible writing style excursions that Lem had returned to the documentary style of his very early works. Lem had tricked me!...The next night I reluctantly open up chapter two and I find myself in the company of totally different characters in a strange world full of unfamiliar technology. We have jumped into the distant future, I don't know how far, and it doesn't really matter. The book takes on a dreamy quality as complex plans and characters are revealed and we are taken on some excursions into the past. I'm not sure why I'm being taken into stories of the past, but I suspect they are metaphorical and are preparing me for the rest of the book. This appears to be the case, but I'm still not quite sure of how I was prepared or what I was prepared for, and this remains one of the mysteries of Fiasco. The tale of the journey through the sea of termite mounds is particularly strange and disturbing. We awake in the future on a gigantic exploratory ship being launched on a journey of hundreds of light years to a star with a retinue of 10 planets. The fifth planet called Quinta has been broadcasting incredibly powerful (but chaotic) radio transmissions that must be signs of intelligent life. This is a mission of "first contact". At times Lem returns to the documentary style to describe the computers, propulsion systems and technology of the future, but unlike Arthur C. Clarke's 3001, it never becomes so tedious that it detracts from the story. Lem likes the themes of detective stories, slowly revealed mysteries and people in extraordinary circumstances, and he draws upon his experience to combine them creatively in Fiasco. When our supremely skilled team of 10 "first contact" specialists arrive at their destination they are unable to establish contact with the Quintans and are confronted with a set of utterly incomprehensible technological mysteries. The planet Quinta is drowned in a cacophony of radio noise, the moon has a flickering plasma ball on its surface, the planet is surrounded by an incomplete ring of ice made by blasting billions of tons of ocean water into space, no moving life is seen on the surface, and they are attacked in a weird and unexpected way. Captain Steerguard asks the question "If you go to visit someone and they will not open the door, do you have the right to blast the door open?". Very slowly the fiasco evolves, but so slowly that it's hard to pinpoint where it starts. The end of Fiasco is one of the most ambiguous and disturbing that I have read in decades. An emissary is finally sent to the surface of Quinta, but he is confronted with a series of incomprehensible signals and landscapes that are so utterly alien that any similar story of "first contact" pales in comparison. I was so unnerved by the story that I reread the last chapter 3 times in one day, and then decided to read the whole book again a week later. Fiasco made me question the limits of my comprehension and imagination, and Lem deserves admiration for stretching my brain so far. To return to a comparison: Lem's Fiasco (1988) and Arthur C. Clark's 3001 The Final Odyssey (1997) are both tales of a Rip Van Winkle character thrown into the distant future. As a fan of Kubrick's 2001 and the original short story The Sentinel , I found 3001 to be somewhat insulting to my memory of these earlier works. Clarke has always had a rather dry documentary style of writing, but this style seems to have have become totally fossilised recently. When describing the dislocation of a character thrown into a distant technological future, Lem simply kicks the shit out of Clarke (and it was written 9 years earlier). |

|

|

|

NOTE (26-Dec-2006) - A review of this book is pending. |

|

|

|

The cover of this paperback portrays the feeling of the early contents wonderfully with an electroknight holding a jousting pole on his cybersteed slaying a robot dragon with a light pistol. Early in the book Lem weaves fairy tales out of worlds inhabited by beings of frozen gasses, gigantic paranoid computers and dragons that eat moons. The last two stories, The Hunt and The Mask are earlier works, I think, and return to more classical style. In one story a machine hunts a man and in the other, man hunts machine. I suspect that these stories were included by publishers to pad the fairy tale stories out into a suitably sized book. |

|

|

|

Lem, writing about himself writing about himself describes his favourite reviews as the ones that are totally abstract, and his least favourite as the one that is a parody of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. Strangely enough, the Joyce parody is one of my favourites, as perhaps the computer programmer inside me is tickled by the idea that the sum total of all human knowledge can be encoded into a literary work like a palimpsest of unlimited depth. The last reviews are the most complex and dense, wherein Lem explores the concepts of artificial personalities and artificial brains of transcendent power. These themes have been explored by Lem in other works in totally different ways: in The Cyberiad we meet the HPLDs (beings of the Highest Possible Level of Development); in Imaginary Magnitude we learn of a computer of the 18th generation that uses a meta-language incomprehensible to humanity. Some of the works reviewed could certainly be the seeds of great real books. A Perfect Vacuum is dense and complex to read, but it's a work of stunning originality that is unlike anything else I've ever read, except perhaps Lem's other related work called Imaginary Magnitude (see the next review). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I haven't read this collection of 5 short stories for about 15 years now, so details are forgotten. We follow the adventures of the astronaut Pirx in a realistic near future where passenger and transport rockets are flying around the solar system. There are some lovely surreal scenes I recall in the last story Terminus where Pirx is taking a decrepit ship on its last journey to the scrap yards in the company of senile robots, a black cat and some mice. Return from The Stars (1961) Also not read for about 15 years. A Rip van Winkle style story of a space traveler who returns home hundreds of years in the future due to relativistic effects during his journey. Bregg finds himself in a totally unfamiliar world populated with a docile and drugged population. The descriptions of 20th century men dealing with the unfamilar future technology, language and customs is reproduced astonishingly well. The Invincible (1964) Like the movie Forbidden Planet, a space ship lands on a bleak and distant world to find out the fate of a previous expedition that vanished. The rescue mission is faced with mounting mysteries as they search through the ruins of an incredibly ancient civilisation. They are attacked by metallic "insects" in swarms the size of thunderclouds and eventually discover that the planet hosted the evolution of non-organic life. This space detective story is quite frightening at times in the horror movie sense, and I keep wondering why no one has picked it up for a movie. Lem's descriptions of the scenery and characters are so vivid that screenwriters would have little more work to do than cut 'n' paste the words from the book straight into a screenplay. Modern CGI effects could recreate the alien world and the epic battles with startling photo realism. |

|

|

Solaris (1961)

Solaris (1961)

I've just finished rereading Solaris as I write this (August 2002), and I'd forgotten how nightmarish it is. All of the characters are creepy and there is an underlying feeling of dread throughout. I remember when I read Solaris for the first time back in the late 70s I thought it was a bit dull and I couldn't understand why it was the work that seeded Lem's fame. Now, 25 years later, I can see deep questions of philosophy and science buried within the story, and the characters (including the ocean) seemed alive in my imagination. I imagine the strange "feel" of the book would have set it apart in the 60s and attracted the fame that Lem deserved. Several years after reading the book again I finally managed to see the 2002 movie remake directed by Steven Soderbergh. I haven't seen the 1972 movie by Tarkovsky since 1979 and all I can remember is its ponderous slow pace. Exactly as I expected, the new movie is basically a romance in space that discards all of the mystery surrounding the planet and its ocean. All of the visions and mystery in the novel have been pushed aside for a tediously long and slow exploration of George Clooney's relationship with his resurrected wife. The new movie has a nice menacing atmosphere throughout, but we never see the planet or ocean up close, despite the fact that CGI effects could have done so wonderfully. Nor are theories of the ocean or its influence discussed in any detail. The ambiguous ending is tastefully done, but I think it differs from the book ending. |

|

|

|

This book could be turned into a fabulous film or TV series, and it would probably finish up like a mixture of Dr. Strangelove, The Matrix and Max Headroom. I recently re-read this book after at least a 10 year gap, and thankfully I had completely forgotten how the story ended. It wasn't until the last few pages that I suddenly remembered the stunning plot twist of the ending which is simultaneously hideous and hilarious. I was reminded partly of the movies They Live (1988) and The Matrix, except of course that Lem, as usual, had given us a vision that surpasses both of those movies. |

|

|

|

Archaeologists of the distant future discover the ruins of the 'The Building' and try to reconstruct what life was like back in the neogene era at the close of the pre-chaotic period. Beware, as rumours abound of an anti-building. |

|

|

|

Six years later, Lem takes a similar idea to its limits and supposes that the background neutrino radiation of the universe is not just random noise, but it contains information, possibly a message. Scientists try to decode the message, which turns out to be very ambiguous and mysterious. We are left wondering if the universe itself is alive, or we are the victims of a cosmic joke, or perhaps humanity is just plain stupid. As usual, Lem has taken the basic premise that our first contact might be with information (a message) and not living creatures and gives it a fresh spin. It's a shame that His Master's Voice isn't as well known as Hoyle's earlier works, or the quite similar 1986 Contact by Carl Sagan. Andromeda was turned into a BBC TV science fiction series in 1961 which was quite atmospheric but suffered from a limited production budget. I would love to see a modern remake of Andromeda or His Master's Voice, each of which could make a fine movie or at least a one hour show in the style of the Outer Limits or Twilight Zone. |

|

|

|

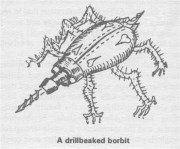

These stories are more subdued that those in The Star Diaries, and many are thoughtful discussions about Lem's favourite question "what is life?" framed via meetings between Ijon and various eccentrics and self-professed geniuses that he meets. There is a side-splitting chapter where Ijon is caught in the escalating battle between two rival washing machine companies trying to produce ever better and smarter models to out sell each other. The last chapter is a great parody of an open letter from conservationists pleading "Let us Save The Universe". After all, how could we live in a universe without creatures like the foul-tailed fetido or the drillbeaked borbit? (see pictures below) |

|

|

|

The story titled The Inquest was filmed for Polish TV, and I only know this because I watched it by accident one night on Australia's SBS Network back in the mid 1980s. Despite the low budget and subtitles, the story snatched my attention and I watched the whole show. At the end of the show, the credits tell me the story was by Stanisław Lem, so I just about slap myself and think "Of course...I should have recognised the style". I remember there is quite a spooky scene were we are looking through the eyes of a humanoid robot (in recorded playback at the inquest) as it clutches a doorway and the gravity is slowly increasing; "tolerance limits exceeded" it flashes just as our viewpoint crashes away backwards. |

|

|

|

Previously reviewed A Perfect Vacuum Previously reviewed The Chain of Chance It might be 20 years since I've read this story, so all I can remember is it's a detective story about finding the links between what seem to be some unrelated deaths. Were the deaths accidental, deliberate or due to some chain of chance? |

Daniel Mróz drawings

Trurl |

Klapaucius |

Pirate Pugg |

The Electronic Bard |

How the World was saved |

Pirate Pugg's demon tape |

The trap of Gargantius |

Human duel |

Evolution |

Other Book Covers

Click the thumbnails to pop-up enlargements. The brown covers belong to hard-cover Secker & Warburg editions that I indented from London via Cosmos Bookshop in St. Kilda back in the early 1980s.

Book Covers/Stanislaw Lem (26)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contents generated on machine OWL by Hoarder 8.0.31.0 on Monday, 01 December 2025 16:59 GMT+11:00

HTML Coding Note

Throughout this web site I have attempted to spell Lem's first name correctly in Polish, as it is shown on the Secker & Warburg covers where the letter 'L'

has a small stroke through it. This special character is defined in the Unicode standard as being hexadecimal 0142 (see the

![]() Latin Extended-A

chart at http://www.unicode.org) Months later I realised that my attention to detail might

backfire, as I was not sure if my Polish spelling would foul-up web searches by people looking for 'Stanislaw' (using the English spelling). The implications of

this issue are still unknown, so in the meantime the English spelling has been placed in a keywords META tag in the HTML headers, just in case this might

overcome any search problems. Technical news on this issue will be posted here when it's available.

Latin Extended-A

chart at http://www.unicode.org) Months later I realised that my attention to detail might

backfire, as I was not sure if my Polish spelling would foul-up web searches by people looking for 'Stanislaw' (using the English spelling). The implications of

this issue are still unknown, so in the meantime the English spelling has been placed in a keywords META tag in the HTML headers, just in case this might

overcome any search problems. Technical news on this issue will be posted here when it's available.